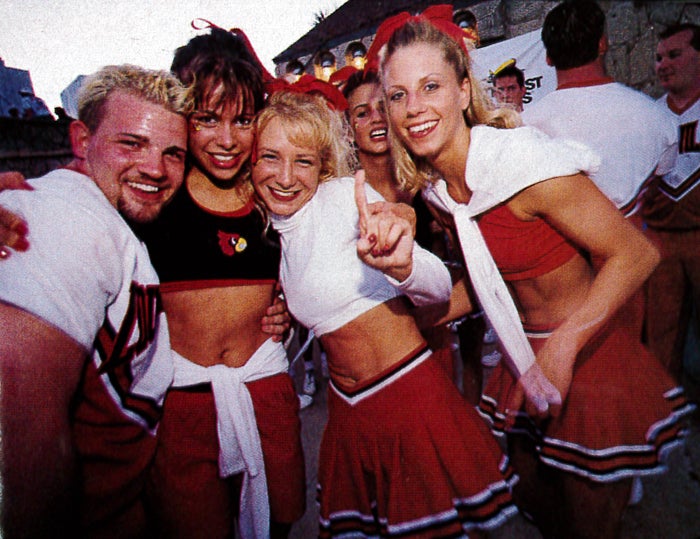

Daytona Beach is a killing field—so smiles, people, smiles! Christie Neal, a University of Louisville cocaptain, looks over at one of the hulking guys on her squad. She knows instinctively that he needs a word of support, for she has the experience. At 22, she has been on two championship teams already, as many as any cheerleader ever. She is blonde and 96 pounds. Her waist, from the looks of it, is seven epidermal layers thicker than a spinal column. She locks eyes with the boy, gauging the type of motivation he requires at this instant. A flurry of ideas and emotions races through her mind until a well-earned wisdom settles across her features. She leans forward; her shoulders recoil and the corners of her mouth begin to burst apart. “Get jiggy with it!” she shrieks instructively. “Get jiiigggyyy with iiiiiitttttt!“

The sun is splintering like something out of Camus, but none of the Louisville girls are sweating. Every sinew beneath their pleated red skirts and black midriff tops is primed and ready to go; there is no hair ribbon out of place, no Cardinal face tattoo that has cracked in the punishing heat. Christie keeps the squad fired up by chanting “U … of L! U … of L!” She calls them into prayer huddles, thanking Jesus for leading them all the way here, to the National Cheerleaders Association championships. “Y’all talk to each other,” she says, grinning into the sun. “If you talk to each other, you won’t have time to worry about your own stuff!”

Having choked in the NCA finals last year, the Louisville cheerleaders have come to this oceanside band shell to reclaim a title they’ve won six times in the past 12 years. Unfortunately, something has gone horribly wrong with the auditorium power supply; the tournament grinds to a halt while electricians work out the bugs in the system. Despite the delay, and with just one team left to perform, no one in the crowd is leaving. They’ve seen plenty of moves that were something-rific; now they want to see something-tastic.

Florida State currently clings to the lead with a score of 8.66. That school’s mascot is a Seminole Indian, as embodied by a glum teenager covered in suede and thick brown makeup. Trapped in the 90-degree heat, he’s looking increasingly like abandoned chocolate. The Louisville squad politely steps around him, alternately hugging and drifting back into huddles.

Huddles are Louisville’s way of preserving their cheer solidarinosc, of being a 20-celled organism that, any moment now, will tumble and fly with a single purpose. When it’s not conferring, the team practices its routine out behind the band shell. During the walk-through, a girl named Amy can contain herself no longer. “Love you all!” she suddenly shouts. The females in the squad shout “love you!” right back. Cheerleader law dictates that no word of support may go unanswered.

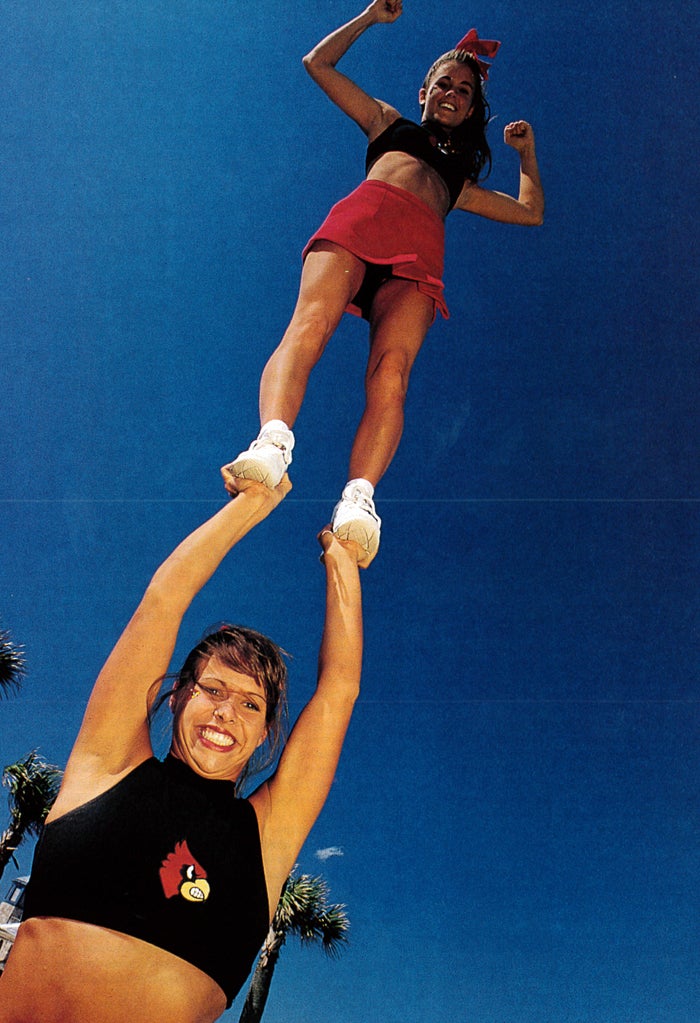

Of course, the team’s practice offers only a hint of the acrobatics to come. Louisville’s routines — and modern cheerleading as a whole — are the bastard child of Bob Fosse and Nadia Comaneci. Soon we will be treated to tumblers careening across the stage and missing one another by a few perfectly timed inches. Girls will grind their hips and beckon us with kinetic, kitten-with-a-whip choreography. Cheerleaders will be held aloft in a dazzling array of star-shaped pyramids, each of which topples as neatly as it rose. There will be “full-up awesomes,” in which girls are pitched upward and garishly stand — stand, on one foot — upon a guy’s uplifted palm. For the first time ever in competition, a female will try a double awesome: She’ll hold two fellow cheerleaders high above her head, one on each hand. “We want to show ’em something new,” says Lynley Wolf, the whiskey-voiced sophomore who will attempt the double. “I learned it a month ago. Up till recently, no one much thought about a girl doing it. It’s unrational.”

In contrast to the tiny females, the boys on the Louisville squad are blocky, with inmate bodies and inmate scowls. They’re like the scene-shifters of Kabuki theater, who dress in black and are thus considered invisible as they do the heavy lifting that makes all illusions possible. Guys, in cheerleading, are the muscle beneath the flesh. Cheer isn’t about males working as spotters. It’s about the girls — their perfect smiles, and the agility beneath the smiles, and the spirit beneath the agility.

All of which lies fallow as Louisville stands and waits. A voice on the loudspeaker promises on no visible evidence that “we will soon be able to wrap up the competition.” As an added taunt, Florida State’s numbers are frozen on the half-lit scoreboard while the technicians puzzle out why everything has gone awry at this climactic moment of the tournament.

James Speed, Louisville’s coach, spins the delay as advantage. “This is great,” he assures his team. “The later it gets, the lower that sun’s gonna go, and it’ll get cooler.”

“I like sun,” says a cheerleader named Scott Foster. “Gives me tan.” Foster has the furrowed brow of a 45-year-old bouncer. He registers joy by looking angry and anger by looking bored. Unless he’s actually performing, he always seems to be scowling at something in the middle distance that’s really pissing him off.

At long last, Louisville is called to the stage; the loudspeaker voice proudly announces that the electrical troubles are over. CBS cameramen, taping the show for broadcast in a few weeks, waddle to their positions. The team takes a single breath. “Nothing affects you,” Speed says, dragging his hand across his balding pate like Robert Duvall. “There is no competition here.”

As she often does, Christie adds pep of her own, this time with a shard of mystifying syntax. “Go the energy,” she tells the squad. “Trust, everybody!”

Louisville jogs out to meet its destiny. The crowd of 8,000 (mainly other cheerleaders who have finished competing) emits a deafening rumble of support. But to everyone’s amazement, the power flickers out yet again — this time because of the sheer amount of electricity that TV cameras require. Louisville bounds offstage one more time. Out back, Lynley Wolf distracts herself by doing back flips on the scalding concrete promenade.

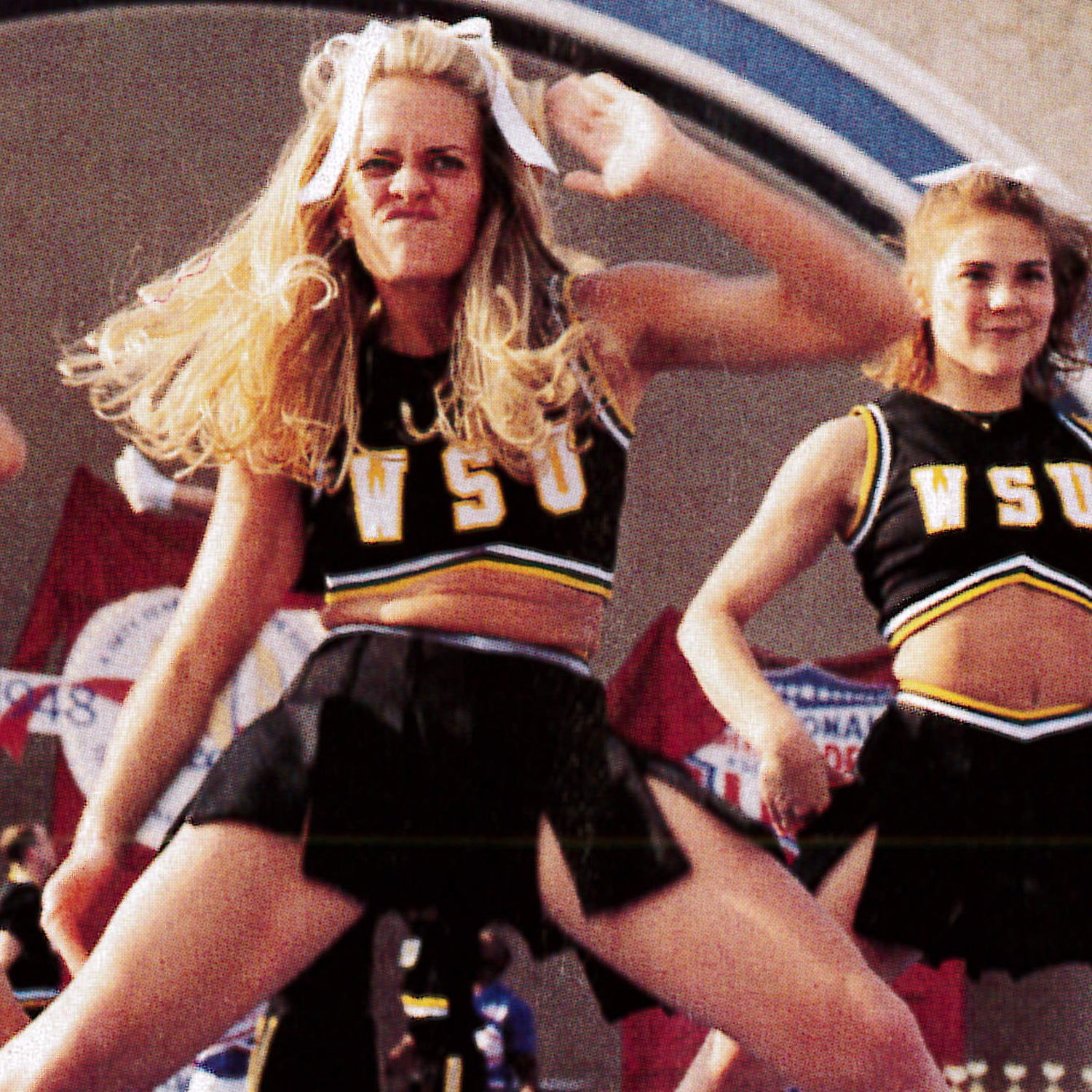

There was an age, not long ago, when cheerleading was a sideshow, a blurring arc of saddle shoes and wool sweaters. The pursuit began in 1865 as something called “yell leading.” Princeton clubs lay claim to the first yell in history: “Tah rah rah! Tiger Tiger Tiger!” (It goes on quite a while from there, and it doesn’t get any better.) But yell-leading would not be organized until exactly 100 years ago, when a Minnesota medical student named Johnny Campbell became a “yell marshal” and made a team of it, augmenting his rhyming ability with familiar old expressions like “Ski-U-Mah.” By the 1950s, girls had joined the fun and acquired pom-poms, which were all too fleetingly known as “shake-a-roos.” It comes as no surprise that Katie Couric, Sally Field, and Raquel Welch were cheerleaders. But who among us would not pay a month’s wage to see the rheumy-eyed antics of Jack Lemmon at Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, the stirringly perky portrayals of Meryl Streep back in Bernardsville, New Jersey, or the spooky levitations of Sissy Spacek?

[quote]Cheerleading makes an important statement about Who You Are in the outside world. Lynley Wolf was hired for her summer job because the company knew she’d be disciplined. They also knew she’d be sharp; cheerleaders must maintain a rock-solid 2.0 average.[/quote]

These days, team spirit can sustain itself without teams. Cheerleading uniforms and training camps are a $200-million-a-year industry. Hundreds of colleges offer scholarships solely for cheer. Louisville awards its top 16 cheerleaders amounts up to $2,000, but there are schools (the University of Memphis, for instance) that dole out full-blown stipends.

Like that other college moneymaker, football, cheerleading can be dangerous. Judged from that dark perch, it’s one of the most athletic pursuits to which students can devote themselves. Between 1982 and 1994, most catastrophically injured female athletes (those killed or paralyzed) were cheerleaders. In 1990, a survey by the Consumer Product Safety Commission found 12,405 injuries, and that was only the number of wounded who showed up in hospital emergency rooms.

Even in Daytona, blood and bruises are commonplace, but the girls are made of tougher stuff. On the day of the finals, while practicing on concrete, a Louisville girl named Megan sustains an impressive gash on the knee. Once Speed bandages it up for her (actually, long before the bleeding is stanched), she is blithely caught up in an unrelated conversation.

Lynley Wolf herself has had countless black eyes, bad sprains, and torn muscles — but she knows three people back home who will never shake off the pain. “They’re paralyzed from the neck down,” she says. “It happens from tumblin’ on grass with rubber shoes, or trying a stunt without the right kind of spotters below you.”

Cheerleading is an undeniably grueling obsession. Working with James Speed in particular is like training for the Olympics with Bela Karolyi. It’s an intense and virtually year-round job — culminating before the NCA championships in two daily sessions lasting as long as four hours each. The team learns to polish each tumble, hit its marks, make things stick.

Speed also plays mind games with his kids, to armor them against the unexpected — just in case, say, their NCA final is delayed by an electrical snafu. Sometimes he orders his tumblers to loosen up, and then forces them to wait an hour before practicing. “James has seen it all,” says Christie Neal, “and he considers it all.”

At 36, Speed is an extremely polite man with a carnivorous grin. Like many of the guys under his tutelage (and TV’s Patrick Duffy!), he was originally lured into cheerleading by a girl he met in school. Today he has won more championships than any living coach. When he strolls through a crowd in Daytona, he doesn’t need to wear a Louisville Cardinals logo; other coaches stop him and clap him on the back, trying to steal some of his winner’s warmth. “Truth is, I don’t know all those guys personally,” he says. “Some of ’em recognize me from TV. In a sport that most coaches burn through in three or five years, I’m an old man.”

Kentucky, of course, is a cheerleader’s paradise. If basketball players walk the streets like gods, cheerleaders are their puny seraphim and cherubim. Given this status as a role model in the community, the Louisville cheerleader must adhere to strict standards of conduct. “We need to maintain an image,” says Christie, mouthing the line as though she has learned it by rote. “We must be presentable both physically and psychologically.”

To live up to this image, she says, “you must be a personality person.” You must carry yourself with respect, knowing that children look up to you — why, they run up to you for autographs! If you smoke, you must smoke in your room, and if you drink, you must drink in your room. In this way, cheerleading makes an important statement about Who You Are in the outside world. Lynley Wolf was hired for her summer job expressly because she’s a cheerleader. The company knew she would be steadfast and disciplined. They also knew she’d be sharp; cheerleaders must maintain a rock-solid 2.0 average.

“School comes first,” Lynley says. “There have been times when I’ve sat down at practice and studied.”

If ever nature designed a cheerleader from scratch, Lynley Wolf is that woman-child. She has spent 14 of her 19 years as a circus performer. “My mom was a ringmaster, but now she just eats fire,” Lynley explains. “We had trainers from Ringling Brothers who taught us German hand-balancing, and others from Bulgaria.”

The circus, for Lynley, was a foray into gymnastics. She was inducted into the American Turners’ Club when she was only three days old, and spent much of her childhood working small carnivals in the Midwest. All of this toil has been part of a grand design. “After college,” she says matter-of-factly, “I hope to work in the accounts receivable department of a major corporation.”

Cheerleading, with its logical culmination in accounting, has offered Lynley a bridge between two worlds. It all comes down to problem-solving and presentation. Christie Neal, too, has her eye on the rough-and-tumble world of finance. “I’m way into marketing and international business,” she says. “You can’t just cheer your whole life!”

The written word bears out these girls’ theories about image. According to the NCA’s almanac on the subject, cheerleaders must be “goodwill ambassadors, spreading positive word about your school.” To reflect this “up” attitude, each member of the Louisville squad wears a penny threaded into the lace of his or her right shoe. The coins are punctured to look like smiley faces; one of the eyeholes has blown out the back of Abe Lincoln’s head (just like in real life!). Every penny is accompanied by a laminated poem called “The Happy Cent.” One of its stanzas reads, “The trials we encounter are many / It is often quite easy to frown / But a touch or a glimpse of my penny / Helps me focus on the good that abounds.”

And the kids find goodness everywhere. Lounging on the pavement a few hours before the finals, they know they’re on the threshold of an experience unlike any other in their young lives. They are partners — family — drawn together not to compete with others but to build confidence in themselves, to be that strange role-model cross between Flo-Jo and Adlai Stevenson.

Somebody heats up the team boom-box, which offers the competitors a moment of repose. Akinyele, a popular hip-hop band, comes on. A blond cheerleader dances to its lilting, bubblegum melody and lip-syncs the lyrics: “Put it in my mouth / My motherfucking mouth / And you can eat me out …” The team grins nostalgically. This is evidently their anthem. The guys take extra pleasure in watching the girl spank herself and act out a portion of the catchy tune that involves swallowing something or other.

“Well, this doesn’t sound like PGA-approved relaxation music!” says Dan Kessler, a 28-year-old assistant coach, widening his eyes to prove he has honestly never, ever heard it before. “This won’t be part of the program!”

There are no kiddies with autograph pads hovering nearby, so the squad enjoys its anthem in peace. The rich imagery of singer Kia Jefferies continues to inspire team unity. But let our Kia speak: “Well you can lick it, you can slick it, you can taste it / I’m talking every drip-drop, don’t you waste it / I’ll be strong once I feel your tongue / In the crack of my ass …” It’s a magical, candyland moment, one these youths will cherish for the rest of their days.

With a childlike awareness of their bodies, the girls drape themselves languidly over the guys, who are rhino-size in comparison. The Florida sun is baking glitter and makeup into their faces as if this were the last stop in a Barbie factory. As they give each other slow back rubs on the sidewalk, there are always a few strangers in sight. Occasionally a man with a camcorder stops by, or a tattooed drifter sits and watches from a clever distance, waiting for one of the girls to drift too far from the pack.

They are natural marks. Cheerleaders, inescapably, are packaged as Lolitas. On the Internet they are a pornographer’s dream. On stage, with their come-and-get-it expressions — always showing a little tongue, just to play to the back of the crowd — they aren’t quite the upstanding citizens their coaches must pretend they are. They are wicked little innocents, shaking it for a culture that applauds innocence and aspires to wickedness.

[quote]In a break with convention, male cheerleaders are being flung in the air as well as females. “They shouldn’t let the guys be fliers,” says one coach, shaking his head in disgust. “You can’t have them doing that on TV. I mean, that’s entirely feminine. It’s gay.”[/quote]

Speed ignores the chaff. He is blind to anything that doesn’t touch the performance of his squad — but that’s what makes Speed Speed. His kids are mature enough to know when to lip-sync and when to achieve. They are not supplicants, having traveled 900 miles in hopes of touching a trophy. Most of them are so psyched up that they regard the NCA finals as a formality. The savvy ones point out that they won in 1992, ’94, and ’96, and that this is an even-numbered year — you figure it out! They just have to do their program as they have thousands of times before. “I know you’re gonna hit your shit,” Speed says, pacing in shade. “Now conserve! Conserve!”

Athletes suffer most when they are at rest. Something about the sting of a muscle at full impact is pleasing to them; pain is the only cure for doubt.

At the band shell, electrical crews have performed nerdy acrobatics of their own, but to no avail. Louisville has been waiting to perform — waiting to make this even-numbered year come true — for almost 90 minutes.

“If something happens,” Speed says, now spouting out random scraps of advice, “you just keep going and win the damn national championship!”

The crowd is restless; time has to be filled somehow. Louisville’s mascot, the Cardinal Bird (named in this redundant way, apparently, to distinguish him from any Cardinal Fish or Cardinal Deer that happens by), amuses the house with some improvised antics. Eventually, cheerleaders in the audience start tossing one another around — but, in a break with convention, males are being flung into the air as well as females. After all the stress and delay, Dan Kessler is finally piqued. “They shouldn’t let the guys be fliers,” he says, shaking his head in disgust. “You can’t have guys doing that on TV. I mean, that’s entirely feminine. It’s gay.”

But as day must follow night, electricity is rediscovered. “OK, let’s go and win this bullshit,” Speed quietly tells the team. “We are too fucking good. Y’all go ahead and pray real quick.”

“Control!” Christie shouts, as if she has suddenly found herself in a wingless plane but is tickled by the challenge. “Con-tro-o-o-lll! Trust Him!”

The guys on the squad are not bashful about seeming competitive. “None of you would let somebody come into your house and take something,” says Scott Foster, looking calm and therefore angry. But Speed cuts him off before he can finish this well-crafted metaphor: “Get out there and have fun.”

At last, the team runs onto the vast blue performance mat. Speed leans on the edge of the stage and watches with a surprising air of impassivity. Now and then he makes an obligatory “woo-woo” sound just to add noise to the crowd’s nihilistic howling. But for the most part he appears to be watching a fond memory on video.

The routine starts with a blur of tumbling and back flips. All at once, the stage is filled with symmetrical chaos. In what’s called a basket toss, two guys pitch a girl 30 feet into the air and watch her do Olympic twists and spins before she falls gracefully back to earth. Five girls are raised into perfectly synchronized full-up awesomes. Seconds later, two girls sail outward and one launches straight up, as if someone at the back of the stage has invented a human fountain.

Throughout the routine, cheerleaders whip the crowd into a frenzy with raise-the-roof gestures and air-humping. There’s even a subtle version of the spanking move that the squad practiced earlier.

The routine clicks. Megan’s bloody knee holds. The performers up front are in top form: now smiling, now making their nasty-girl faces, all timed on a razor’s edge. How a cheerleader smiles — straight ahead, as if she’s gazing out toward a wonderful future in accounts receivable — makes up a whole discipline of the sport, “facials.” Christie is the greatest sincere-smiler of her generation, while Lynley favors a sultry pout. But they are equally jiggy.

As the routine comes to its bombastic close, Lynley steps to the front of the stage and pulls off the double awesome as second nature. Without so much as creasing her brow from the effort, she holds two girls aloft and casts them off, raising her fists in triumph. Even this well-versed crowd doesn’t seem to fully appreciate how powerful she is.

Slowly, like a lion watching a kill, Speed shows his teeth. He senses a seventh trophy, a new addition for the three-tiered, 42-foot-long display case back in his Louisville gym.

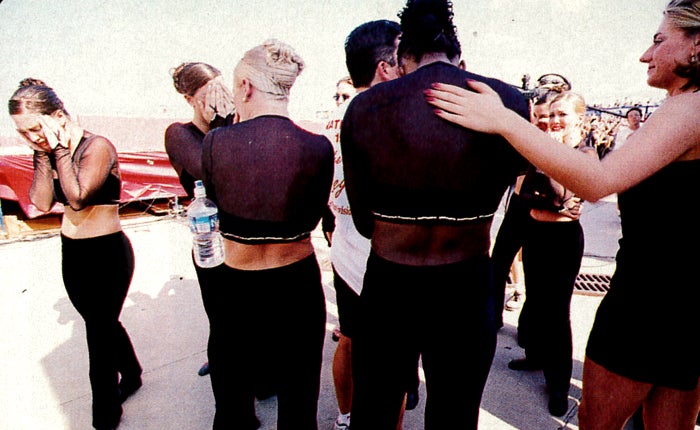

The team scurries back to the safety of a huddle. A male cheerleader with prominent cheekbones is weeping. Lynley looks dazed. Christie, too, seems stunned, and anchors herself by hugging anything that moves.

The crowd waits for scores to tell the tale. Florida State’s Seminoles encircle their sticky brown mascot, while Louisville surrounds its Cardinal Bird. The judges wait an extra beat for drama before revealing the numbers, so Louisville sneaks in another prayer-quickie.

Apparently, Jesus is a fan. Louisville pulls an astonishing 9.16, one of the few times in NCA history that any team has broken the 9.0 mark. The one deduction has occurred because of an imperceptibly muffed cradle-catch near the beginning of the program. Now everyone is weeping except James Speed, who keeps himself polite and composed for a CBS interview. Scott Foster, looking extremely angry, is carrying a tiny weeper around by the waist, as if he won her at one of Lynley’s carnivals.

Christie blinks slowly, realizing that she has set a personal record at this event. “I’m the first girl,” she says, covering her perma-smile with babyhands. “I’m the first girl ever to have three!”

Not all the cheerleaders in Daytona are happy, of course. One squad huddles primarily to muffle its crying. A Cameron Diaz lookalike sobs so noisily that even the melting Seminole helplessly looks around for someone to console her.

For other teams, there’s always next spring. For Louisville, there will always be tonight. Thirty years from now, the girls’ smiles will be marked by fulfillment or nicotine or defeat, but tonight they are exquisitely blank. Their whole world, for this one moment, is swathed in Cardinal red. And the only sound anyone can hear is a roar of jubilation from the crowd, which is giving its own aimless cheering an encore ovation.