Picasso's Balance of Opposites

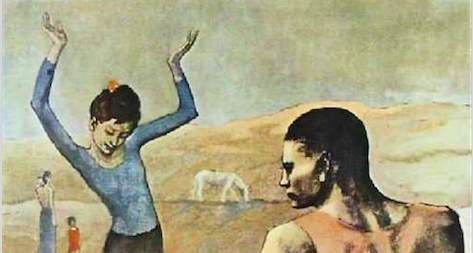

Picasso’s Young Acrobat on a Ball, completed in Spring 1905, focuses on the dynamic of opposites, in content and in form. The work contrasts in content, through the acrobat balancing on a ball and the man sitting on a cube. It also contrasts in form, through lines, shapes, and color, which emphasize the lightness of the acrobat and the heaviness of the male figure.

In this composition, horizontal and vertical lines, much like thick and thin forms, are in contrast. The focus of the work is on the cube and on the sphere, on which the young acrobat is exhibiting her lightness and balance. Furthermore, the landscape is a natural, rural countryside, yet there are no distinguishing features or landmarks in the background. It is almost a non-place. The acrobat’s hands occupy part of the empty space above the horizon and balance the void. The delicacy and gracefulness of her hands make them seem to float in the blank sky and form a square, which balances the cube in the right foreground.

Movement and stillness, heaviness and lightness, involvement and disengagement are few of the contrasts represented. Density functions as an expression of power. The male figure’s scale is greater than the acrobat’s, which suggests authority and control, yet it is static and inert. Picasso’s exploration of the subject of the acrobat during this period is extensive. Moreover, he is inspired by the Impressionist works by Degas, who depicted ballet dancers. While Degas depicts ballerinas in a distinct context and background, such as a ballet studio or a stage, Picasso chooses a non-place landscape, a land of nowhere. Unlike ballet dancers, who are hired by specific companies and are based mainly in one town, acrobats do not settle in a specific location. As a result, they belong to a non-specific land, like nomads. Furthermore, acrobats are perceived as outsiders, because of their familiarity with wild animals, such as apes, and their ability to work with them. The strength, flexibility, balance, and grace of the acrobat make her appear almost non-human. Picasso might have been intrigued by these qualities.

Just like the composition, the colors used in the work, mainly blue and brown, carry meaning. Although the male’s proportions belong to the foreground, the brown color pushes him to the background. The sky is grey, almost blue, and similar to a flat surface, which contrasts with the depth of the hilly landscape in brown shades. Red is scarcely but thoughtfully used here. This color appears only on the acrobat’s hairband and on the dress worn by the young figure in the background. The source of light is external and undefined, and it originates from the left, almost horizontally oriented, similar to that of a sunset.

The technique, on the other hand, plays with the viewer’s expectations. Picasso used oil paint for this work, with a variety of brushes and techniques. However, on top of the dense, flat layers of a dark shade he applied a lighter tone, in a sketchy manner. This technique is shown on the man’s garment, where blue is roughly laid out over black. Although the main technique is oil on canvas, it evokes the stain-like effect of gouache. The treatment of color on forms, such as the man’s head and nose, show that the artist designed shadows with an intense, pigmented black tint, which appears liquid. Subsequently, Picasso blurred and softened the harsh profiles with a dry brush or even his fingers. Furthermore, technique plays with the viewer’s expectations in the treatment of the empty background to the right margin, next to the man’s torso. Picasso provokes the viewer by showing him that he is in front of a flat canvas. A surface in a thick, light tint over a black wash effaces any attempt to depict a shadow, depth or perspective. This empty space flattens out the background, enhances the manly torso, and contradicts the viewer’s expectation of perspective.

The man sitting on a cube is static, and his body complements the shape of the cube, making it appear as an extension of his body. His left knee partially hides the sphere on which the acrobat is standing and contrasts with the round shape of the ball. However, the calf muscle closes the sphere line and creates an interesting visual over-imposition. The man’s back is massive, muscled and marble-like. This gives a sense of heaviness, rigidity, and authority. This is further enhanced by his muscular leg which is bent in the foreground. Picasso plays with the square and the sphere as basic geometric elements; the square can be linked to the earth, while the sphere to air or water. The acrobat belongs to the lightness of the air, while the man belongs to the gravity of the earth. He is stuck in his own physicality, not engaged nor entertained in the acrobat’s freedom of movement. Moreover, this dynamic of lightness and heaviness can be extended to the contrast between femininity and masculinity. Additionally, the acrobat’s gesture of her hands seems to invoke something from the sky. It is unclear whether she is just balancing her weight or also praying. The long religious tradition of depicting hands in a similar gesture is associated figures praying. Nonetheless, the acrobat evokes a sense of lightness but also spirituality: her head rises above the horizon line and into the sky, while the man’s head remains below it. Unlike the acrobat, the male figure is monolithic. His muscled torso, arms legs suggest a potentially powerful body. Yet, his eyes, his stance and the cube below him declare his powerlessness.

Picasso’s Young Acrobat on a Ball plays with the means of representation by breaking down the idea of light and heavy, of material and immaterial, and of the natural elements. Just like the acrobat on the ball, Picasso balances empty and non-empty spaces, to emphasize tension between the opposites. The gracefulness of the acrobat, reaching to the sky, and the airy treatment of her lines and shapes almost gives her a non-human, spiritual value. On the other hand, the massive, sculpture-like man is fixed in his earthly condition. His self-containment and disengagement with the acrobat’s performance accentuates the impossibility of change and progress, stuck in his own gravity. His weight, scale and authority counterbalances the flexible, slender and delicate acrobat.

In conclusion, Picasso wants to transform Degas’ ballerina into an acrobat, emphasizing the nature of non-human, and spiritual figure in a non-place. Picasso encourages the viewer to step away from the traditional ‘Degas-type-of-painting’, and enter a more unconventional, experimental art. The two opposites of the acrobat and male figure represent a paradox of modernity, where rigidity and impotence contrast with the search for freedom and spirituality.

Unicorn breeder at Edwards & Praly

5yWhat a long but interesting way to say : I like this painting, which is the only thing I could say ;-)

Polyglot | Hospitality Specialist

6yFeel free to send me a feedback and/or share this article with colleagues and friends!