As you eat food every day, you can easily feel the digestive process and the renewal of energy that results. What you can’t feel, however, are the multiple chemical processes that take nutrition from food to energy. By now, you’re likely already aware that the process of glycolysis breaks down sugars into usable products that can be chemically converted into energy. In this AP® Biology Crash Course, we’ll talk about the Krebs Cycle, the process by which those products produce ATP.

The Krebs Cycle (also known as the Citric Acid Cycle or Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle) is the metabolic process by which aerobic organisms produce energy in the form of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). The process takes place within the mitochondrial matrix—the liquid found inside the mitochondrion of the cell—and comprises multiple sequential chemical reactions that release products like carbon dioxide, FADH2, ATP, and NADH.

We’ll discuss these reactions and products as they pertain to AP® Biology in more detail later. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the chemistry involved, however, let’s go back in time—way back—to prehistoric Earth.

From Prehistoric Origins

Imagine life on Earth in its earliest stages: simple, single-celled organisms, like bacteria, respiring and creating changes in the planet’s atmosphere. But how did these organisms function and create energy for themselves? We know that today’s aerobic life relies on the Krebs Cycle for metabolism, so it’s hypothesized that this cycle developed far, far back—perhaps in the so-called “primordial soup” of Earth’s past.

The Krebs Cycle is hypothesized to have potentially originated from anaerobic bacteria. Scientists speculate that these bacteria have been using glycolysis to create energy from as early as 3.5 billion years ago, when there was insufficient oxygen for what we imagine to be “normal” respiration. Once oxygen became more readily available in the atmosphere (approximately 2.7 billion years ago), processes like photosynthesis began to develop. The Krebs Cycle itself is somewhat new to organic life—it’s thought to have appeared around 1.5 billion years ago, when eukaryotes finally developed cellular respiration.

We won’t go too far into the details of life’s beginnings in this AP® Biology Crash Course, but it’s important to know that the Krebs Cycle is thought to have come from the random, regular reactions of chemical monomers in the early stages of organic matter. Once this process had developed and begun producing ATP, living organisms would have been capable of forming and producing energy.

To learn more about Earth’s early environment and the beginnings of organic life, be sure to check out our Abiogenesis AP® Biology Crash Course when you’re finished with this one!

Chemistry of the Krebs Cycle

As you know by now, cellular respiration isn’t as simple as “sugar goes in, energy comes out.” Since this is AP® Biology and not AP® Chemistry, you won’t need to know the exact processes of chemical synthesis and breakdown involved in each stage of the Krebs Cycle, but you will need to have an understanding of how inputs change into outputs while catalyzing other processes along the way.

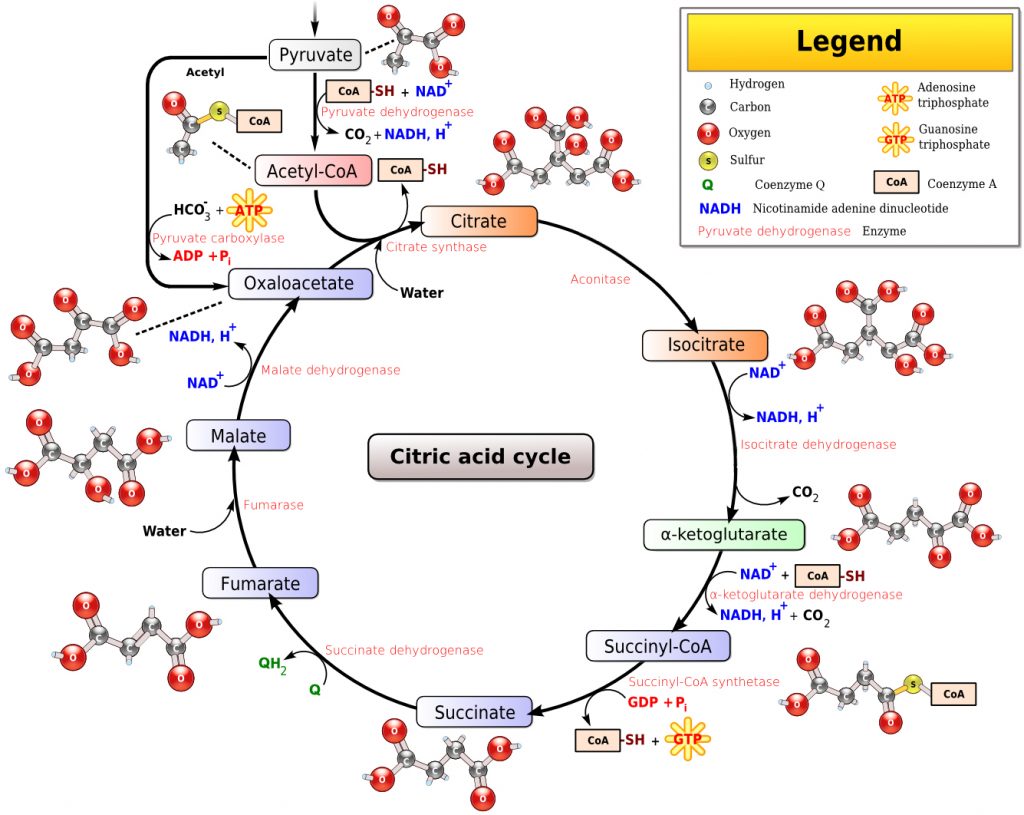

Look at the following diagram for the overall process of the Krebs Cycle (and stay calm)! We’ll break it down step-by-step after the graphic.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

It may look overwhelming at first, but if we break the Krebs Cycle down into its component steps, it’s not so difficult. Let’s take it one reaction at a time, and feel free to refer to the diagram again to get a visual idea of each step.

- Acetyl CoA reacts with oxaloacetic acid (OAA) to form citrate.

- Citrate loses two carboxyl groups, releasing CO2and becoming

- Isocitrate is oxidized, releasing CO2. At this stage, NAD+ is converted to NADH.

- α-ketoglutarate is oxidized, again converting NAD+ to NADH and releasing CO2. The molecule that remains then becomes succinyl CoA.

- Succinyl CoA loses its CoA and picks up a phosphate group. This phosphate group transfers to ADP to produce ATP.

- Succinate is oxidized and becomes fumarate. Two hydrogen atoms then transfer to FAD to convert it to FADH2.

- H2O attaches to fumarate, converting it into malate.

- At the end of the cycle, OAA has been reformed, and one more molecule of NAD+ is converted to NADH. The OAA is then fed back into the beginning step to continue the cycle.

Note that these steps comprise one “turn” of the Krebs cycle. To break down the two acetyl CoA molecules produced from a single glucose molecule, two turns of the cycle are required.

While it might sound abstract when described in this way, the result of the Krebs Cycle is easy to see in daily life; the CO2 that is released from the process is the same CO2 that we exhale when breathing.

Now, we have an idea of the overall steps of the Krebs Cycle. This isn’t an AP® Chemistry crash course, however, so it may seem somewhat obscure to say that “ADP becomes ATP.” In the next section, let’s take a closer look at the process by which energy is actually created from this cycle.

Chemiosis

The steps of the cycle aren’t all you’ll need to know for the AP® Biology test. Chemiosis—or chemiosmosis—is the primary mechanism of energy coupling and is, therefore, responsible for producing the actual ATP in the respiration process.

Chemiosis takes place within the membrane of the mitochondrion, where protons are pumped through channels to produce what is known as a proton gradient. Loose protons (or hydrogen atoms) diffuse down this gradient via ATP synthase, a transport protein that helps them cross through the mitochondrial membrane. This flow of hydrogen ions is what catalyzes the pairing of phosphate with ADP to form the ATP produced in cellular respiration.

AP® Bio Exam Review &Practice

- The Krebs Cycle, also known as the Citric Acid Cycle or Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle, is a series of chemical reactions that produce ATP as part of the metabolism of aerobic organisms. It takes place after glycolysis and is a key element of cellular respiration.

- The Krebs Cycle is believed to have developed during the earliest stages of organic matter (around 1.5 billion years ago), possibly as part of the basis for life on Earth.

- The steps of the Krebs Cycle are as follows:

- Acetyl CoA + oxaloacetic acid (OAA) formcitrate.

- Citrate becomes isocitrate.

- Isocitrate is oxidized. CO2is released, and NAD+ is converted to NADH.

- α-ketoglutarate is oxidized. CO2 is released, and NAD+ is converted to NADH. Succinyl CoA remains.

- Succinyl CoA loses CoA and gains a phosphate group, which transfers and converts ADP to ATP.

- Succinate becomes fumarate. FAD is converted to FADH2.

- H2O converts fumarate into malate.

- NAD+ is converted to NADH and OAA reforms to be fed back into the cycle.

- Each glucose molecule produces two molecules of acetyl CoA; therefore, two turns of the Krebs Cycle are required to break down a single molecule of glucose (per-glucose yield is twice the amount of products from a single turn of the cycle).

- Chemiosis is the process by which energy is coupled, and ATP is produced from ADP. The transport protein ATP Synthase allows the transport of protons/hydrogen atoms across the mitochondrial membrane, which creates a proton gradient. The flow of hydrogen ions down this gradient is what catalyzes the attachment of phosphate to ADP to produce ATP.

Well, that’s it. The Krebs Cycle might have seemed daunting at first, but it wasn’t as bad as you expected, was it? If you haven’t quite got it down yet, don’t give up! This AP® Biology Crash Course isn’t going anywhere, and you can always continue to review the steps of the cycle until you know it.

If you think you’re ready to take on the AP® Bio Exam, however, give this practice question a try:

Q: Describe the purpose of the Krebs Cycle and name its inputs and products.

A: The Krebs Cycle serves as a major metabolic process in aerobic organisms and produces chemical energy from sugars. Inputs include two Acetyl CoA molecules (from a single glucose molecule), and outputs include ATP, CO2, FADH2, and NADH.

Need help preparing for your AP® Biology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Biology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.