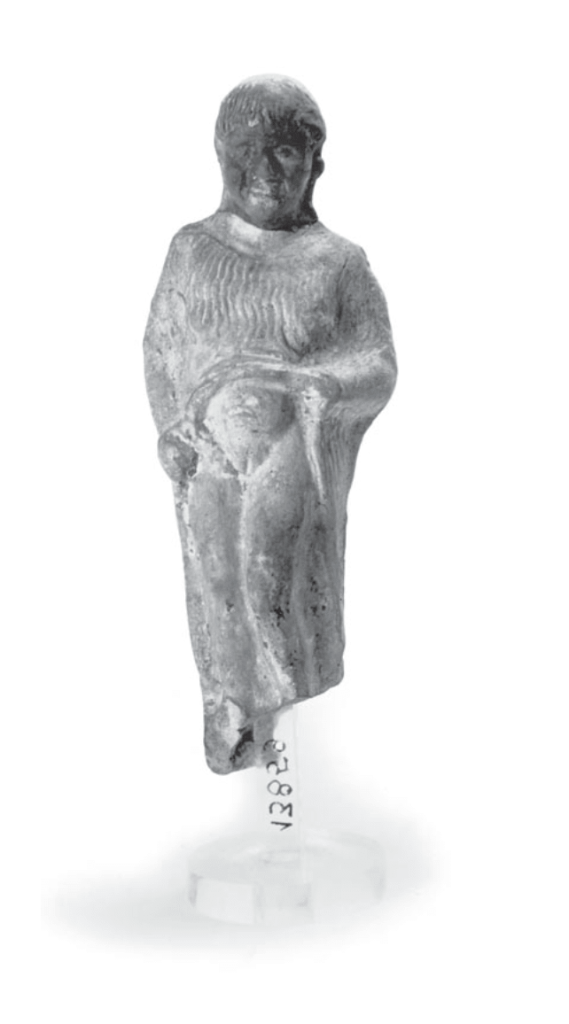

In 1898, a group of German archaeologists working in the Demeter sanctuary at Priene unearthed a peculiar set of Hellenistic female figurines. The head of each of these figurines sits directly on her legs. Each figure also has long hair that drapes around her back resembling a lifted veil. These figures represent Baubo.

The Story of the Great Goddess

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter, written in the 7th century BC, has a few lines about Baubo. These lines tell the story of how the Eleusinian Mysteries, the greatest mystery of the ancient world, came to be. About 1450 BC, these mysteries began to be celebrated at Eleusis, which is near where Athens is now. They went on for about 2,000 years, until the sanctuary was completely destroyed in the 5th century AD.

Baubo’s past is a bit of a mystery because people aren’t allowed to talk about the ancient mysteries of Demeter, in which she plays a big role. Because of this, the only people who know anything about her are theologians who are against the rituals of pagan religions. Modern scholars added to these ideas over time to fill in the gaps that were left by the silence around the Eleusinian mysteries.

Demeter was walking around the world because she was sad about her daughter Kore, who had been taken by Hades, the god of the underworld, in a violent way. Demeter hid in the city of Eleusis by pretending to be an old woman. She was soon invited into the king’s home.

Everyone in the king’s household tried to cheer up the sad old woman, but they all failed until Baubo came. Baubo said some funny and risqué things, which made Demeter laugh. Then, Baubo lifted her skirt in front of Demeter, which made Demeter laugh long and hard. Different versions of this story show what Demeter saw under Baubo’s skirt, but whatever it was, it helped her get out of her bad mood. With her confidence and mood back, Demeter persuaded Zeus to tell Hades to release her daughter.

The Lost Origin of the Great Goddess

The origin of Baubo dates back to a very long time ago in the Mediterranean area, especially in western Syria. Eventually, her identity became a mix of that of older goddesses like Atargatis from northern Syria and Cybele from Asia Minor. As it is likely that Baubo started out as a goddess of plants, her role as a servant in the myths of Demeter may have been a sign of the change from a hunter-gatherer culture to an agrarian one in which Demeter, the Greek goddess of grains and the harvest, took over.

The crown Baubo wears tells us a lot about who she really is. Baubo’s headdress is two big, double acorns that stick out a lot. If the crown tells what the person wearing it does, like all other crowns worn by gods do, then it is safe to say that Baubo is an old god from a culture before agriculture.

Acorns were the main food source for thousands of years, before people learned how to plant and harvest crops to make more food. Even after farming was invented, acorns were still very important to the people who lived in the early lake dwelling settlements in Central Europe, the northern Scandinavian countries, and the British Isles.

Some people in the Mediterranean area continued to eat acorns when times were hard, while others thought of them as a treat. People thought that the tree’s roots went all the way down into the underworld because they were so deep. So, a dark and ancient link was made between the fallen acorns on the forest floor and the creatures that hung out there in the fall to eat the fruit that fell to the ground.

Celeus (Keleos) is the name for the green woodpecker (Picus viridis). Ovid’s Fasti, book 4, tells us that the aged ruler: “carried home acorns and blackberries, knocked from bramble bushes, and dry wood to feed the blazing hearth.” It is in this version of the story that the woodpecker-king: “halted, despite the load he bore,” to greet the grieving old woman at the well.

The arboreal green woodpecker is best known as a weather prophet, and a rain-bird, because its loud cry is said to warn of impending rain. The Greek name Keleos literally means ‘to cry’, or ‘call’, sometimes with specific reference to one who calls out orders or commands, such as a god. Classicist Robert Graves described this aged king as a sorcerer. However, Celeus never become a god. His role became eclipsed by a powerful invading god of thunder and lightning, the patriarchal sky-god Zeus. Zeus also adopts Demeter’s sacred oak as his own tree, thus obliterating Demeter’s role as the goddess of the oak and queen of the ancient woodlands. However, Demeter’s earlier role is preserved in Ovid’s telling of the sacrilege of Erysichthon in his Metamorphoses, book 8:

“It is said he violated with an impious axe

Metamorphoses, book 8

the sacred grove of Ceres, and he cut

her trees with iron. Long-standing in her grove

there grew an ancient oak tree, spread so wide,

alone it seemed a standing forest; and

its trunk and branches held memorials,

as, fillets, tablets, garlands, witnessing

how many prayers the goddess Ceres granted.”

The sacrilege made the oldest oak in Ceres’s sacred grove tremble and moan. Its leaves and acorns turned white, and the colour left its long branches. It is also a good example of how Zeus usually acts, which is violent. Long before the beginning of the Eleusinian story, Zeus had already slept with Demeter, which gave birth to Kore, who later became the reason for Demeter’s sad wanderings.

Zeus kept getting in the way after that. In the Homeric Hymn, he was the one who set up for Kore to marry her uncle Hades, the ruler of the underworld, without her knowing. Kore later changed her name to Persephone. This line of incestuous relationships points to the rule of matrilineal descent, which said that a male god’s power could only be kept if he married into the female line. So, when Kore and Hades got married, the power went from the matriarchy to the patriarchy, which was led by Zeus. But taking this power by force is a big problem for the matriarchal status quo. In the end, Demeter was not only a sad mother because she had lost her daughter, but she was also a traumatised great goddess because she had lost her daughter, her power, and the world as she knew it.

Demeter went into King Celeus’s house in a dark cloak. As soon as Demeter walked through the door, her light shone out of the darkness and lit up everyone who was there. Demeter kept quiet until Baubo did something silly that made her laugh. This is another way in which the Acorn Mother (Baubo) gives power to the Goddess of the Grain (Demeter). Unfortunately, wise Baubo also becomes Demeter’s Fool at this very moment.

People have written a lot about what Baubo said and did. But her very brief mention in these lines of the Homeric Hymn doesn’t tell us anything useful about what she did for the goddess. Only the fact that it worked is known. Homer calls her Iambe and says that she was a court jester and then Demeter’s fool or jester in the Mysteries at Eleusis. She is the first fool written about who is a woman, and she may be as old in oral history as the first court jester written about. She is even older than Danga, the Egyptian fool of Pepi II, who lived from 2325 BC to 2150 BC and could “dance the God, distract the court, and make the King’s heart rejoice.”

The Journey of the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone

At first, only women could experience the mysteries of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis. They were coming-of-age ceremonies that mirrored the phases of the moon in a woman’s life as a young woman, mother, and old woman. The nine days of initiation rituals at Eleusis started in the last third of the month and probably went on until the crescent of the new moon appeared in the sky. From the time Kore disappeared (the maiden), when Demeter started her sad wanderings (the mother), until she arrived at Keleai as an old woman (the crone), this has been a story about the moon going away and wandering.

As the initiates made their way from Athens to Eleusis, they stopped on a bridge to take a break. On the bridge, funny jokes and strange games called gephyrismoi kept the procession amused (bridge jests). There were different stories about who did these shows. It could have been a woman, a hetaera, who was a courtesan or mistress in ancient Greece, or it could have been a man, a gallus, who had his testicles cut off and was dressed as a woman. As Baubo, the performer encouraged the initiates to join her in making sexual comments and gestures, like lifting their skirts for the crowd to see. This action is similar to a sacred move made by ancient goddesses who would only show their secrets to people who had been “initiated.” That is, they would literally pull back the veil to show a secret. This event helped the mystai get over their sadness (the initiates).

Scholars think that Baubo’s strange appearance, which shows her mouth and belly next to each other, is a sign of her sexually lewd behaviour. However, Baubo’s appearance is more likely a reference to her power over the food supply. Because of how holy Demeter’s rituals are, no one knows what this priestess who reveals herself actually says or does. This makes it too easy for people in our modern society to think that it is just rude.

The fact that Christian influences seem to favour a sexual interpretation of Baubo’s behaviour demeans her sacred role by making her look like a crippled old woman who tells dirty jokes and makes lewd gestures. This would have moved the focus below her belly, which would have led to translations of Baubo like one from 1893 that says, “That which the woman showed to Demeter, that is, the female pudenda.” This statement has become the most common thing that scholars say today. In Protrepticus, Clement writes: “I will quote you the very lines of Orpheus, in order that you may have the originator of the mysteries as witness of their shamelessness”:

”… she drew aside her robes, and showed

A sight of shame; child Iacchos was there,

And laughing, plunged his hand below her breasts

Then smiled the Goddess, in her heart she smiled,

And drank the draught from out the glancing cup.”

Unfortunately, influential scholars have relied on the words of church fathers such as Clement of Alexandria (150 – 211 AD) and Arnobius (255 – 330 AD) for nearly 20 centuries. Thus is the sacred Fool of Demeter transformed in the written record, losing sight of her original status. The first fool, Baubo became the butt of many jokes. That is the fate of fools even thousands of years later.

This was a wonderful read. I think that it’s a shame the world has forgotten the Belly Goddess. I did not know about the ties to acorns, which is neat. Anyway, thanks for the good for thought. I’m always grateful for a good read.

LikeLike

My pleasure! I’m glad you like it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person